Abstract

Sappho (600-570 BCE) was a talented Greek Lyric Poet. Unfortunately, today she is either known at an academic level of discourse or as an LGBTQ+ icon. However, neither of these interests fully engage with the beauty of her work. This experiential I.S. project entitled ‘Playing Sappho’ uses a website with a blog and ‘How-To’ videos to engage in the re-creation and participation of Sappho’s work with particular attention to the Hymn to Aphrodite and Fragment 16. I also evaluate modern interpretations and translations of Sappho. The website blog highlights my process and challenges; it also showcases how to build your own lyre and how to sing in ancient Greek, in order to allow a wider public to appreciate Sappho’s work. My project allows for a greater level of public interaction and ensures that site visitors can experiment with their own Sapphic performances. Through this it is my hope that Sappho’s beautiful work might be widely sung again.

Sappho’s Background and Context:

According to legend, the head of Orpheus washed up on Lesbos’s shores bringing with it his talent for music, and by extension the lyre.1Warren D. Anderson, Music and Musicians in Ancient Greece, (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1994) 28 This began a long and storied tradition of music on Lesbos in the Ancient Greek world. Sappho was part of this tradition, and the reason for this myth may be to explain Lesbos’s connections to lyric poetry in the archaic Greek past.2 Ibid Sappho was far from the only famous lyric poet from Lesbos; Terpander, another lyric poet who supposedly built the 7 string lyre was from Lesbos as was Pindar.3 Ibid, 36. A lyre that in some way is perhaps the ancient ancestor/ model of the ones built in this project 4Ibid, 62. The island enjoyed a rich musical past, and was innovative in its early lyric poetry, most likely influenced by the ‘Ionian mainland’ it was so closely connected to, and at times ruled.5 Ibid To better understand Sappho, and the musical world she inhabited, it is important to place Lesbos, and the archaic period in context.

Though Lesbos is a separate and distinct island today, in antiquity it was closely linked to Asia minor, and by extension what ancient Greeks considered ‘the eastern’ world. So much so that some scholars argue it should be considered not as a separate island in antiquity, but as a part of a larger whole, composed of other cities from Greek speaking peoples on the eastern mainland.6Aneurin Ellis-Evans, The Kingdom of Priam: Lesbos and the Troad Between Anatolia and the Aegean, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019) 56 Archeological evidence suggests that the Lesbos of Sappho’s time, controlled land on the Asian mainland as a regional colonial power.7 Christy Constantakopoulou, The Dance of the Islands: Insularity, Networks, the Athenian Empire and the Aegean World, (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2007) 240 It is even theorized by the relative lack of monuments from ancient Mytilene that the polis spent so much time and resources on maintaining an ‘empire’ of sorts that the polis had no resources to build monuments.8 Ibid, 241. It is also worth noting that the first image of a recognizable seven stringed lyre is found in an ancient settlement known as ‘old Smyrna’, in modern day turkey.9 Warren D. Anderson, Music and Musicians in Ancient Greece, (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1994) 10 It is theorized that the lyre, and different forms of musical innovation came from the east, into Lesbos, and from there into Greece.10 Jane McIntosh Snyder, “The Barbitos in teh Classical Period,” The Classical Journal 67, no.4 (1972): 334 All of this contributes to the idea that Sappho’s home served as a link from the wider eastern world to the Greek speaking one. Sappho is then positioned at both the right place and time to be at the forefront of this musical innovation.

Sappho lived in the Archaic Period, a time period defined by scholars as roughly the 8th to the 5th century BCE.11 David Mulroy, Early Greek Lyric,(Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1992) 1The archaic period is one of immense change, and innovation.12 Ibid, 3 Cults and rituals are codified and more thoroughly established.13Ibid, 8 Institutions that would shape the rest of the Hellenistic world for centuries to come began to take form. It is a period of intense progress, change, and upheaval. One of the most notable cultural changes was the development of Lyric poetry.

Sappho was a lyric poet, she would have sung her songs while playing a lyre or kithara. Lyric poets engaged in what modern scholars define as ‘Lyric Poetry’ a specific genre of musical style and performance that developed during the archaic period. Loosely defined, Lyric Poetry is the ancient Greek practice of singing composed metrical poems with instrumental accompaniment.14 Warren D. Anderson, Music and Musicians in Ancient Greece,(Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1994) 58 Mulroy notes in Early Greek Lyric Poetry the term ‘lyric poetry is best understood as one used to distinguish between epic work in dactylic hexameter’.15David Mulroy, Early Greek Lyric, (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press 1992) 1 He further states that ‘the ancient Greeks made no distinction between lyric poetry and song’.16 Ibid 9 This is useful to keep in mind as today most Lyric poetry is represented as written poems, rather than song lyrics with lost melodies.17 Ibid There is debate on how early lyric poets performed, and in what societal contexts they functioned. For Sappho this is especially complicated.

Sappho and Her Performance Within the World of Greek Lyric Poetry

Very little about the life and experiences about early archaic lyric poets survive into the modern world. This is especially complicated for Sappho, because what a woman’s life would have been like in the archaic period is unclear. It is equally unclear how a lyric poetess would have performed, and in what context. Sappho was a prolific composer of song, though only a few fragments remain of her work today. She created works of monody, and choral song, and her work would have most likely been invoked at weddings, religious rites, and certain public events.18 Warren D. Anderson, Music and Musicians in Ancient Greece, (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1994) 72 Anything more than this vague outline is lost to time. Sappho is significant not because she is a woman, but because she is an exceptionally talented one. Her gender, and how that limited and defined her work is still up to debate, but her skill is not. For Sappho’s male contemporaries their roles are a little clearer. Men had more agency than women in the ancient world, and many of the places and occasions it is understood that men performed in, it is presumed that Sappho would never have been permitted to partake in. Whatever details of her life, and how she performed are lost to time, Sappho’s innovative and intimate style became a model for many later artists, hundreds of years after her. Yet Sappho was not the only womanly voice singing against a chorus of men in the ancient world.

Sappho was one of many other poetesses in the ancient world, but she is one of the few whose work survives. Despite present day appearances Sappho is not an outlier. In reality Sappho is just the sole example of a larger tradition of women poets in the archaic Mediterranean .19 Sarah B. Pomeroy, Goddesses, Whores, Wives, and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity, (New York: Schocken Books, 1995) 56 Her perception as an exception is not helped by the fact that as a woman Sappho is often minimalized. David Campbell in his compendium of Greek Lyric Poetry sums up Sappho as a domestic, intimate performer who performed for close friends. As Campbell states ‘Of her own life, we know little, perhaps because there was little to tell’.20 David A. Campbell, Greek Lyric Poetry, (Great Britain: Bristol, Bristol Classical Press, 1982) 261 Sappho’s work speaks of exile, virginity, mourning, and much more, and this is just what survives in the fragments of her work. She seems to have engaged in a wide range of human experience, and though it cannot be definitively stated that Sappho’s speaker represents her life, I do believe that she had a lot to say. The archaic period was one of intense culture flourishing, but also upheaval, which Sappho’s songs reflect. As a woman, her position would have been even more precarious than that of a man with more agency, which also works against the notion of a ‘quiet life’. Yet as a woman Sappho cannot be fully categorized in a system that largely only conceptualizes of men, which encompasses much of the scholarship done on Greek lyric. Further complicating things is her at times taboo subject matter, Sappho’s erotic work is something that many find impossible to accept or understand.21 Judith P. Hallet,”Sappho in Her Social Context: Sense and Sensuality,” Signs 4, no.3 (1979):450. I will not be engaging with what the erotic nature of Sappho’s work means, and for more on this please consult the About page. I will say that I find Anne Carsons’s approach to accept Sappho’s erotic nature without controversy or comment (‘It seems that she knew and loved women as deeply as she did music. Can we leave the matter there?’, Anne Carson, “Introduction,” in If Not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho, by Sappho, trans. Anne Carson (New York: Alfred A. Knopf publishing, 2002)x) very compelling Sappho defies convention even as she lives inside it, and refuses to be categorized. It’s part of the reason so little is known about her today, even though she was not unique being a poetess in the ancient world, she is difficult to define.

However, some definition is necessary to understand her performance, it is important to understand the ‘known’ facts, such as they are. Sappho’s surviving work seems to consist of love songs, epithalamia, and songs that might have been used in public festivals for the gods.22 David Mulroy, Early Greek Lyric, (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1992) 87. Epithalamia were songs composed for a bride on her wedding day. Sappho’s work has literary styles of both monody (a song by one speaker) and choral songs.23 Ibid 24It is important to note that as André Lardinois says in his chapter “Who Sang Sappho’s Songs?”, in Reading Sappho: Contemporary Approaches, Classics and Contemporary Thought Vol 2., ed. Ellen Greene, 150-172 (Berkely: University of California Press 1996) 150; ‘There is no concrete division between solo and choral song’ There is a debate about who ‘truly’ performed Sappho’s works, either Sappho herself or someone imitating her, or how they were performed. One pervading idea of Sappho’s performance is that it occurred within the context of Sappho teaching a chorus of young women, or girls.25 David Mulroy, Early Greek Lyric, (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1992) 87 Though Mulroy notes there is no evidence for this claim, Campbell echoes the assertion that Sappho had small private performances for other women. Though as Mulroy notes there is no evidence for this claim, it is a lingering idea.26 IbidSuch debates are beyond the concerns of Sappho’s performance, and thus this project, but they are important to note. Judith P. Hallet is also of the opinion that Sappho did encourage a young group of girls in performance, but saw Sappho’s role as a mentor who taught and showcased young women ‘sexual self-esteem.’ 27 Judith P. Hallet, “Sappho and Her Social Context: Sense and Sensuality,” Signs 4 no.3 (1979):456 André Lardinois concurs that Sappho was the choral leader in a group of young women, but argues that her performance was part of a public social ritual, not a private one.28 André Lardinois “Who Sang Sappho’s Songs?” in Reading Sappho: Contemporary Approaches, Classics and Contemporary Thought Vol.2, ed. Ellen Greene, 150-172 (Berkley: University of California Press)156 Lardinois states three different performance type for Sappho’s songs: “She sang while a chorus of young women danced… The young women did both the singing and the dancing…. Exchanges between Sappho or another soloist and the group”.29Ibid 170 Lardinois also stresses the public nature of these performances, arguing against a private school mistress group.30 Ibid 154. While there can be no definite idea of Sappho’s performance, Lardinois’s argument is strong. He takes textual evidence, and contemporary historical accounts of male lyric poets and women’s groups in ancient Greece to make his argument. Lardinois concludes that Sappho’s lyric was part of a broader sphere of public performance for both men and women. Lardinois makes a compelling argument, as he understands Sappho not as an aberration but as part of a larger social context. The fact remains that Sappho has a gendered treatment when it comes to her male counterparts, many of her actions or limitations are presumed based on her gender. As much more work by male lyric poets survives, more is understood about their work.

Lyric poetry from a male context is better known than what existed for Sappho. History records her male counterparts better, though ideas of the early Lyric poets are still incomplete. In contrast to personal matters, many male poets composed songs about war, military, and physical strength. Male lyric poets are understood by scholars as to have had public political work and performances, often set in contrast to Sappho’s perceived personal compositions. 31 David Mulroy, Early Greek Lyric, (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1992) 9. Though Sapph did write about personal matters, there is no reason to think personal matters cannot be political, or that she was necessarily speaking about herself, and the tendency to assume that Sappho sang about her own heartbreaks for friends is not base don any solid evidence. Lyric poets who happened to be men performed chorally in musical competitions, at different sporting events, celebrations for the gods, and victory odes.32 Ibid, 10-11 In solo performances men performed at banquets and symposia.33Ibid Anderson analyzes the male lyric poet Alcaeus, a fellow lesbian and contemporary to Sappho, as her foil. Noting ‘His work was often political, in contrast to most of Sappho’s work which is largely about personal matters’.34 Warren D. Anderson, Music and Musicians in Ancient Greece, (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1994) 74 In contrast to this, Lardinois compares Sappho to a different male lyric poet, Alcman, and his public performance; arguing they reflect different areas of public life for men and women.35 André Lardinois, “Who Sang Sappho’s Songs?” in Reading Sappho: Contemporary Approaches, Classics and Contemporary Thought Vol.2, ed. Ellen Greene, 150-172 (Berkley: University of California Press) 156 Additionally, Sappho’s perception as being apolitical and domestic in part may be due to the vast majority of her work being lost. Sappho’s gender continues to complicate analysis of her work, but it also complicates understanding of what spaces her performance was allowed to occupy. Spaces that men could freely move in become much more controversial for Sappho.

Male choral lyric performers would have performed in symposia, or drinking parties, and it is assumed that Sappho was barred from such places because of gender. Scholars such as Mulroy and Anderson assert this, as do many others. 36 Warren D. Anderson, Music and Musicians in Ancient Greece, (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1994) 58 37David Mulroy, Early Greek Lyric, (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press) 87 Anderson cites Sappho’s lack of access to symposia as one of the reasons Sappho does not compose political poetry, which was often made at such parties. 38 Warren D. Anderson Music and Musicians in Ancient Greece (Ithaca: Cornell University Press) 74. It is important to remember that just because it is not extant or currently found that does not mean Sappho composed no political songs. With Sappho it is impossible to argue for a negative absolute. As it is not currently known what she did, it cannot be fully argued what she did not do. This notion has been challenged recently. Ewan Bowie in his chapter in the Newest Sappho argues that Sappho was a performer in Symposia .39Ewen Bowie, “How Did Sappho’s Songs Get into the Male Sympotic Repertoire?” in The Newest Sappho, P. Sapph Obbink and P.GC inv. 105, frs 1-4: Studies in Archaic and Classical Greek Song, Vol.2, ed. by Anton Bierl , and André Lardinois, 148-166. (Boston: Brill, 2016) 151. As Bowie’s evidence rests on vase imagery from classical Athens, I do not think he can truly apply it to Sappho, and I do not think he has sufficient evidence to make the claims he does. While I do not agree with Ewen Bowie’s argument because of his evidence, I think the notion that Sappho would not have been immediately excluded from Symposia because of her gender does need to be challenged, and I would not rule out the hypothesis entirely. Bowie uses vase imagery of Sappho from classical Athens and literary testimony from Sappho’s male counterparts to assert his claim. Ibid 150 Bowie argues against Lardinois’s theories about public performance, by arguing for the ‘semi-private’ space of the symposium. This theory is an intriguing one; Bowie provides a needed new perspective on Sappho’s gender limitations and how that affected her performance.

Much like the theories of Sappho’s life, her performance is also murky and up to debate. No real answer may be found here, but by examining different theories it is possible to allow for different conceptions of Sappho, and different embodied Sapphos. I am of the mind that Sappho in translation, either in the context of ancient Greek to English, or cultural translation from the shores of ancient Lesbos to now, is a singer with many different voices. Sappho today has many different performances, whatever she once had in the past, just as she has many different ways of singing today.

An Overview of the Barbitos Within its Cultural Context, and Design Conclusions on My Final Barbitos

The barbitos is a specific type of lyra, popular in the archaic period up until the 4th century.40 Martha Maas and Jane McIntosh Snyder, Stringed Insturments of Ancient Greece, (Massachuesetts, West Hanover: Yale University Press 1989) 127The ancient Greek word, βάρβιτος, comes into Greek very late.41 Jane McIntosh Snyder, “The Barbitos in the Classical Period,” The Classical Journal 67, no. 4 (1972):331 As an instrument it seems to have ties to the east, to modern day Turkey.42 IbidAs previously mentioned, some scholars, such as Jane Snyder in her article “the barbitos in the classical period” hypothesize that the barbitos has eastern origins.43 Ibid 44Warren D. Anderson, Music and Musicians in Ancient Greece, (Ithaca: Cornell University Press 1994) 76, Anderson also echoes this point. 45Stefan Hagel, Ancient Greek Music: A New Technical History, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009) 412 This assumption is due to the etymology of the word barbitos, and also the fact that many ancient historians associated it with the east. 46Jane McIntosh Snyder, “The Barbitos in the Classical Period,” The Classical Journal 67 no.4 (1972):332 Sappho never uses the word ‘barbitos’ in her poetry, but one possible theory for this is that the word barbitos enters ancient Greek very late.47 IbidThere is also the chance that the name barbitos was ‘applied to the long armed lyre later’ than Sappho’s time.48 Warren D. Anderson, Music and Musicians in Ancient Greece, (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1994) 75Whatever Sappho’s association, the barbitos is heavily associated with Lesbos, and by extension what an ancient Greek mind would have considered ‘the east’.49 Ibid 62 Evidence suggests that the barbitos, or its ancestors started in the east, came through lesbos, where it is heavily associated with many artists, and came into the rest of Greece from there.50 Jane McIntosh Snyder, “The Barbitos in the Classical Period,” The Classical Journal 67, no. 4 (1972): 334

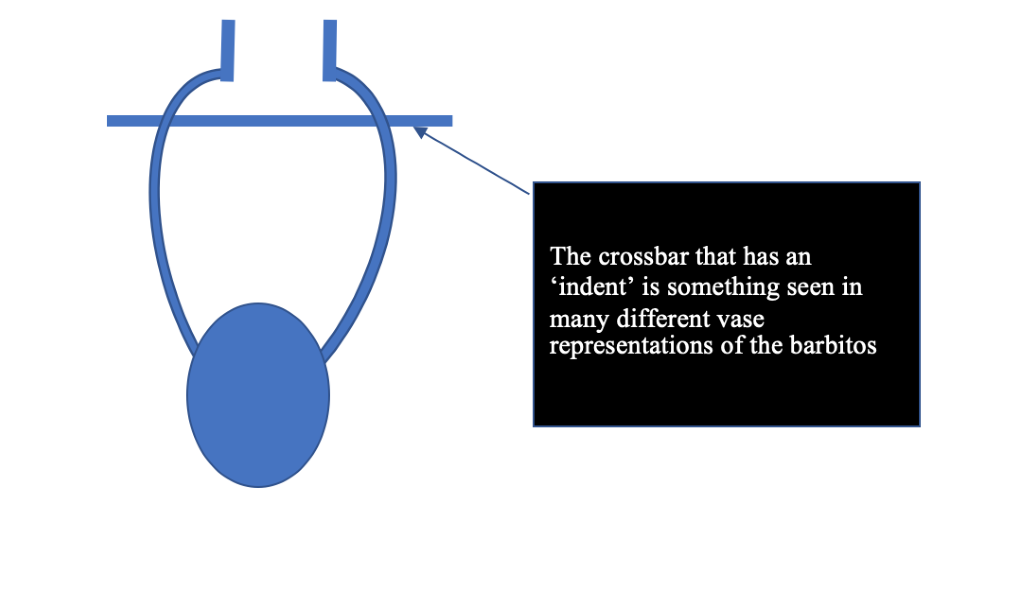

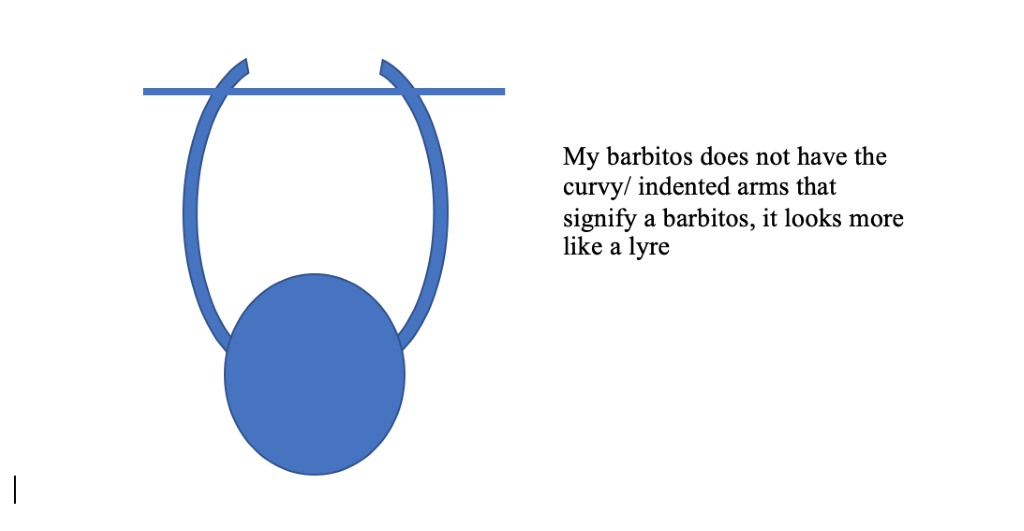

The barbitos exists as one of many lyra a generic term for ancient Greek stringed instrument.51 Martha Maas, and Jane McIntosh Snyder, Stringed Instrumens of Ancient Greece, (Massachuesetss, West Hanover: Yale University Press, 1989) 114It existed with a chelys, what Anderson calls ‘the lyre proper’.52Warren D. Anderson, Music and Musicians in Ancient Greece, (Ithaca: Cornell University Press , 1994) 13The chelys was also a lyre composed of a goatskin and tortoise shell drum, with two parallel arms the strings are suspended from. The barbitos is similar to the chelys, but it has much longer arms, making it lower pitched.53 Ibid 73 It also has a distinctive arm shape that curves out and inwards. aperture.54 Martha Maas and Jane McIntosh Snyder, Stringed Instruments of Ancient Greece, (Massachuesetts, West Hanover: Yale University Press , 1989) 124 Roberts refers to it as a ‘bass lyre’, in reference to its much longer arms and strings giving it lower tones.55 Helen Roberts,”The Technique of Playing Ancient Greek Instruments of the Lyre Type,” in The British Museum Yearbook 4: Music and Civilization, ed. by T.C. Mitchell, 43-76. (Great Britain: London, British Museum Publications, 1980) 43 It also has a distinctive arm shape that curves out and inwards. 56Martha Maas, and Jane McIntosh Snyder, Stringed Instruments of Ancient Greece, (Massachuesets, West Hanover: Yale University Press 1989) 124My barbitos, because of issues with design execution and understanding, resembles a very large chelys more than it does a barbitos.

The barbitos was used in a larger system of Greek music. As mentioned on my About page, ancient Greek music is incredibly complex. It is based on different systems of notations and scales, one for the vocal register, and one for instrumental scales.57 Stefan Hagel, Ancient Greek Music: A New Technical History, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009) 2How it functions in Sappho’s time, as accompaniment to her music, or to craft melodies in general is completely unknown. Almost no evidence survives of ancient Greek musical notation in the archaic period.58 Ibid 391This means that my performance is largely based on my own experimentation of what sounds good, though scholars like Helen Roberts, Martha Maas and Jane McIntosh Snyder do posit different theories of playing the barbitos, they are from a 5th century perspective.59 Martha Maas, and Jane McIntosh Snyder, Stringed Instruments of Ancient Greece, (Massachusetts: West Hanover, Yale University Press 1989) 116 As it stands my skill is not incredibly advanced, but how I strike the strings is determined on the line I am performing. If it is composed of short stressed vowels, I play a higher sounding note to accompany it, or if it is longer ‘heavier’ sounding consonants I go with a lower note. I follow the convention of sounding a line with lyre, I do not play while I am singing.60 Helen Roberts, “The Technique of Playing Anicent Greek Instruments of the Lyre Type,” in The British Museum Yearbook 4: Music and Civilization, ed. by T.C. Mitchell, 43-76. (Great Britain: London, British Museum Publications, 1980) 44 I am not an expert in ancient Greek music, and have already expounded on the virtues of Stefan Hagel’s book for those looking for a more technical understanding. My performance, while well researched, and passionate is far from the ‘real thing’.

My Project as a Work of Public History, and My Ideological Framework for the Playing Sappho Project as a Re-Creation

It is important to place the Playing Sappho Project in its proper context. This project is not an ‘authentic’ re-creation of a Sappho’s lyric performance. Rather, I use the framing provided by Amy Tyson in her chapter in ‘A Companion to Public History’.61 A Companion to Public History, ed. by David Dean, (John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2018)Tyson is a historian whose work focuses on oral history, and public history. Tyson has focuses on pageantry and representations of race in colonial setting. Her chapter, “Reenacting and Reimagining the Past,” is a study on colonial re-enactors in North America. 62 A.M. Tyson, “Reenacting and Reimagining the Past,” in A Companion to Public History, ed. by David Dean, 351-364 (John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2018) 352 The analysis of colonial reenactments is beyond the Playing Sappho Project, but Tyson provides a useful ideological framework for contextualizing this project. She examines how different colonial reenactors perform, but also why they perform. Tyson notes that the reenactment of the past concerns the wants and needs of the present, and those engaging in different re-enacting activities.63 Ibid 351I then use this framework to establish my present-day concerns and limitations and how they have affected my work, rather than trying to establish the Playing Sappho Project as a model of ‘authenticity’. I acknowledge that my main goal with this project was to make Sappho’s art accessible for everyone, within the constraints of a two-semester project. These goals and constraints have shaped the outcome of my performance. Additionally, I acknowledge that I have a certain affection for the ancient past, and focus purely on the beauty of Sappho’s work.

I have prioritized the building of an instrument associated with her, but as I have stated previously I chose this instrument for the relative ease of which you can build it. I chose it because it is relatively easy to re-create, though even the barbitos I make out of salad bowls, or turtle instead of tortoise shells are far from accurate. This is due to errors in design and execution on my part, but also a lack of ancient materials or techniques. I chose to give it 7 strings because that seemed the most common number of strings the barbitos had, and I was also recommended to do so by experts (such as Stefan Hagel). I made mistakes in my designs, which did not compromise the sound but I ended up with a barbitos that looks more like a very large lyre or chelys rather than a true barbitos. When it comes to the song itself, I have had similar issues of recreation, I am not a talented vocalist. I have attempted to find a compromise in my performance between my singing in Pitch meter and what sounds good to a modern ear. As a result, my ancient Greek song sounds neither wholly Greek or modern. I also acknowledge that the fragments I have chosen to sing would have been performed together, they are just some of my favorites. All of these decisions result in a performance that is more based on my decisions skills and resources than Sappho; especially acknowledging that her performance was most likely choral and public in nature, while mine is not.

In this Project I am also engaging with Vanessa Agnew’s ideas of re-creating the far past. Agnew is a historian who focuses on issues of reenactment, genocide, exile, and music. In her chapter in A Companion to Public History, Agnew examines re-creations of different Paleolithic ice-age experiences.64 Vanessa Agnew, “Reenacting the Stone Age: Journeying Back in Time Through the Uckermark and Western Pomerania,” in A Companion to Public History, ed. by David Dean, 365-374 (John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2018) 365I acknowledge that the re-creation Agnew studies are different than the archaic period; Sappho’s time gives many different literary and archeological sources, while the ice age has none of the former and few of the latter. Nevertheless, Agnew’s framework is useful to analyze Sappho’s archaic one, as there are some gaps in the written record concerning Sappho, her work, and her performance. I do this because most re-creations are based upon events closer to the current day and for which there is more evidence. Agnew in her chapter examines different ways reality TV shows and hunter gatherer seminars. She states that these events of re-creation are part of a modern day impulse to return search for ‘a time less tainted and more primal’ in the ancient past.65 Ibid While Agnew’s re-creation differs from mine in many ways it is helpful to acknowledge and understand that the ancient past is often viewed as a better world than present day. Admittedly Sappho, who both praises and creates beauty represents this idealized past by allowing me (and hopefully others) to escape the troubled present, with a well-built lyre, and a well sung song. Yet I reject such extreme nostalgia in my own project. My aim is to not idealize Sappho, or use her to ‘return to a better time’. My aim is to showcase her beautiful work.

This results in not a ‘true’ recreation of Sappho’s work, but a re-creation that I have executed despite limited time, resource, and ability. I will be continuing this project past the completion of my Senior Independent Study, so I will hopefully improve on all of the choices I have made, but for now this is where it stands. My recreation reveals a present more concerned with simply engaging with a notion of the past, and making notions of the past available to others than ‘getting the past right’. I have cobbled together a concept of Sapphic Performance, though it is far from ‘true’. I hope it suffices in conveying Sappho’s beauty.

Literary Analysis of Sappho’s Hymn to Aphrodite

A note before two translations of Sappho’s ‘Hymn to Aphrodite’66 It is also known as the ‘Ode to Aphrodite’ and Fragment 1are examined. As briefly outlined in the About Page, Sappho was s part of a wave of a new art form, Lyric Poetry. Her work is poetic and inventive, but almost always maintains a strict structure of line and form. Sappho uses a rigid structure of meter, along with inventive word play to communicate her thoughts. Her songs are incredibly talented pieces of art, which display her considerable skill. The following is an in depth look at her only current complete song extant, known as the Hymn to Aphrodite.

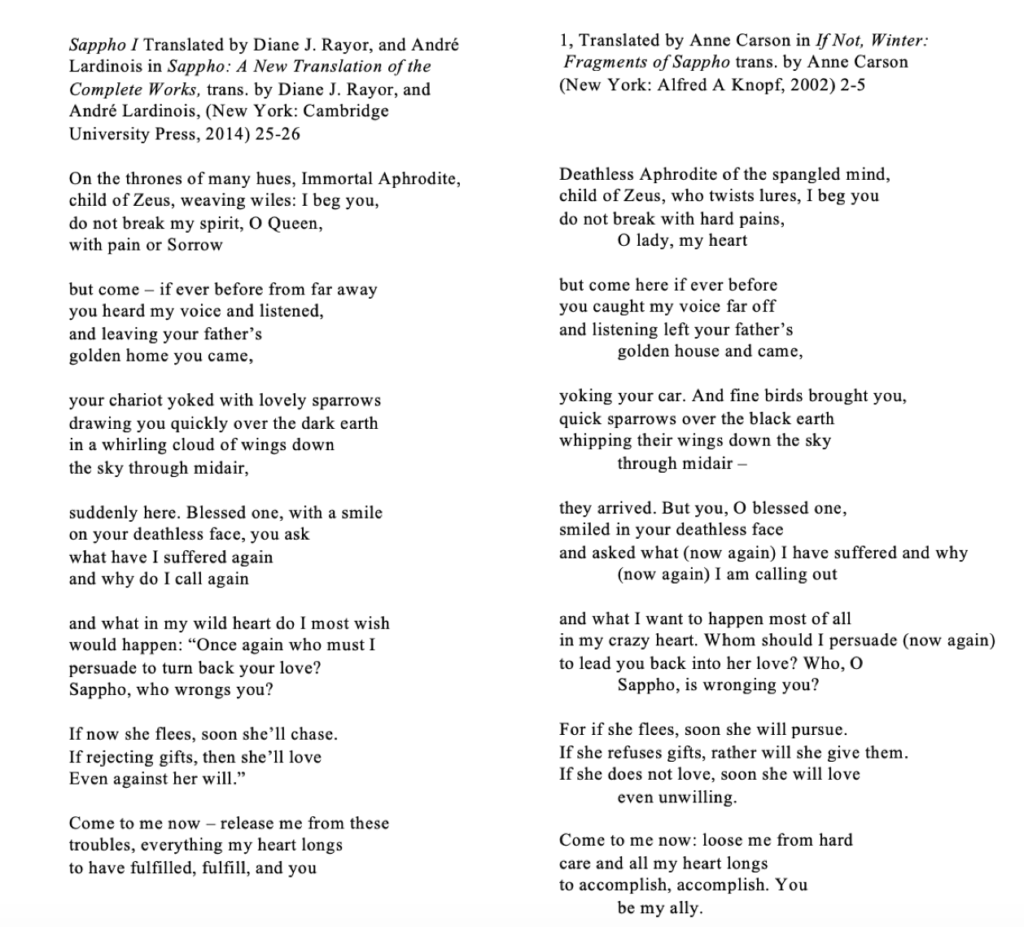

Sappho’s Hymn to Aphrodite is the only complete song of Sappho’s that remains today, which makes it a good example for both examining Sappho’s lyric skill, and how different translations can create different readings of the same text. The two translations above are both by skilled classicists, and show how many different English interpretations of Sappho there can be. In each translation, choices were made based on what each translator felt was important to emphasize in the English. In bringing ancient Greek into the English, the translators had to make certain decisions on what and how to prioritize information, and how to convey that in a lyrical sense that retained some of the Greek feeling. This is a task further complicated by the source text.

Ancient Greek is an incredibly descriptive language, that like Sappho allows for a multiplicity of interpretations. As a brief example, the ancient Greek word for ‘word’ ‘Ὁ Λογος᾽ (Logos) has over fifty definitions, and can mean anything from math formula to law, fact, speech or story.67Lidell and Scott’s Greek English Lexicon, s.v., ὀ λογός᾽, accessed February 25th That is just an arbitrary example out of thousands, as much as Greek words have a multiplicity of meanings, English words often do not. This adds complexity to translating, because ‘choosing’ one sense of a word over another can affect the sense of a whole translation. In addition to this, Sappho’s Aeolic Greek can be even more challenging to understand. All this means is that when translating Sappho there is a high degree of variability between different English translations, there is no one ‘right’ Sappho. Instead, she must be understood as coming into English in many different voices. To better illustrate this, I will be examining both translations, as well as analyzing the first stanza of Sappho’s Hymn to Aphrodite.

I will begin by analyzing the translation on the left, composed by Diane Rayor and André Lardinois. Lardinois is a specialist in early Greek poetry and drama. His work has focused on analyzing Sappho in her larger cultural context, and her performance. Rayor is a noted classicist whose work has focused on women in antiquity, and has published extensively on Sappho, and has made different translated volumes of her work. Rayor in her chapter ‘Notes on Translation’ in Sappho: A New Translation of the Complete Works68 Sappho, Sappho: A New Translation of the Complete Works trans by Diane J. Rayor and André Lardinois (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014) states her goals as a translator include ‘accuracy and poetry’ as well as retaining the original sound of the Greek. Rayor states that she strived to create an English poem that was readily understood, as well as that prioritized ease of reading, while attempting to make the song understood better lyrically in English.69 Diane Rayor, “Notes on the translation,” in Sappho: A New Translation of the Complete Works trans by Diane J. Rayor and André Lardinous (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014) 21 Rayor consistently refers to Sappho’s works as ‘songs’ rather than how an English reader would understand them as a poem. The transition from sung work to a media that exists almost exclusively on the page is something that Rayor is also aware of. In her chapter in The Newest Sappho Rayor states three guiding principles for translation from Ancient Greek into English should be ‘1) the translation invokes the absent song. 2) The translation reads as poetry. 3) The translation evokes the physical fragment on worn or torn papyrus.’70 Diane Rayor, “Reimagining the Fragments of Sappho Through Translation,” in The Newest Sappho: P. Sapph. Ibbink and P. GC Inv. 105, Frs. 1-4: Studies in Archaic and Classical Greek Song, Vol.2, ed by Bierl Anton and André Lardinois, 396-412 (Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2016) 397 Rayor’s chapter is concerned with the translations of fragments, and the Hymn to Aphrodite is no fragment, but her principles of translation still apply. Rayor also notes a distinction between how translating into English is also the work of composing a poem into English.71 Ibid, 396

In this framework, translators can be viewed as another level of composition of Sappho’s work, another voice ‘signing’ or writing her words, in another way. I do not have one firm view for analyzing translations of Sappho, but this is a useful ideology for understanding her translations in context. Rayor is also concerned with word sound, and how the stanzas ‘look’ mimicking the text on the original manuscript.72 Ibid 397 The translation done by Rayor and Lardinois is very easy to read, and flows well as a written English poem. Of course, as Sappho was originally performed, this is another layer of translation, from spoken to written word. Carson has similar concerns as Rayor in her translation.

Anne Carson’s translation is on the right, and though Carson emphasizes different things in her translation, it is also a good representation of Sappho’s hymn to Aphrodite. Carson is also a classicist, as well as a poet, which leads to different priorities in style and transmission than Rayor. Carson’s translation is interesting in that it seeks to retain a deep sense of the ancient Greek in the English translation. She uses English phrases that retain a sense of the archaic Greek, in that to a native English speaker they seem old, or odd. Carson reproduces the original Greek on each page opposite of the English translation, underscoring the ancient Greek origin of the translation. Like Rayor, she is also concerned with representing the original manuscript in a visual poem, and again like Rayor she uses stanza breaks and indents to convey this.73 Ibid Her use of the Greek in conjunction with the poem as a visual medium underscores this. Carson is also a poet, and her work (to me at least) reads as more playful and lyrical, she experiments with the literal sense of the ancient Greek, word choice, and how to utilize English to create a composition that does not seem wholly English. It seems like the foreign song which it is.

Both translations are works done by incredibly skilled scholars, and both are worthy translations of Sappho’s work. They are similar, but do not mimic each other, even though they are based on the same text. This difference does not mean one is more or less valid; Carson’s translation would be very helpful for someone with rudimentary understanding of Sappho or Greek (and her text is the first Text of Sappho I ever read). Rayor’s might be better for someone who unfamiliar with either, but can enjoy the beauty of the work. Neither can fully re-create the original, as I cannot fully re-create Sappho’s performance, but both showcase Sappho’s beauty. To better understand the specific decisions made in each translation, I engage in a deeper examination of both translations and the original Greek.

Taking a moment to analyze further, I am looking at the first stanza of the Greek, then re-examining how Rayor and Carson translated it. Here is the first stanze of the Hymn to Aphrodite in its original ancient Greek:

ποικιλόθρον’ ἀθανάτ Ἀφρόδιτα,

παῖ Δίος δολόπλοκε, λίσσομαί σε,

μή μ’ ἄσαισι μηδ’ ὀνίαισι δάμνα,

πότνια, θῦμον

It’s also worth remembering that Sapphic Greek is different than much extant ancient Greek; it’s archaic Aeolian Greek. It’s difficult to understand, the language itself is very old. This is how Sappho begins her only extant complete poem (for now, more could be discovered). Sappho’s speaker begins her song with an invocation to the Goddess Aphrodite, and the rest of the work is organized around her bargaining with the goddess. This is not completely unusual, as the song are organized like a prayer, a woman named Sappho is asking Aphrodite to aid her in love.74 David A. Campbell, Greek Lyric Poetry, (Great Britain: Bristol, Bristol Classical Press, 1982) 264 75 Though as Rayor notes there is no gaurentee the speaker is sappho. Diane Rayor, introduction to, Sappho: A New Translation of the Complete Works, trans by Daine J. Rayor and André Lardinois (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014) 14Rayor and Lardinois argue that it would have been performed in public.76 Diane Rayor and André Lardinois, notes to, Sappho: A New Translation of the Complete Works, trans by Diane J. Rayor, and André Lardinois (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014) 97What is interesting from a point of translation is that the epithet that the poem’s speaker addresses the goddess is difficult to translate, and due to different manuscripts there is no definitive text to decide.

Rayor and Lardinois, along with Campbell, take the first word of the Hymn to Aphrodite to be ‘ποικιλόθρον’ (poikilothron). This word is an epithet that begins Sappho’s address to Aphrodite, which her speaker will continue throughout the poem. To begin a song, perhaps something used in public ritual, to a goddess, a good powerful word is needed. Rayor and Lardinois render ποικιλόθρον as ‘on the throne of many hues’ citing that Olympian gods are often ‘depicted sitting on multi-colored thrones’.77 Ibid In their interpretation, Aphrodite is thus addressed in her form as powerful goddess, with reference to a literal emblem of her power – a throne. This reading is supported by David A. Campbell, who also uses the word ‘ποικιλόθρον’ which Campbell also reads it as ‘multihued throne’.78 David A. Campbell, Greek Lyric Poetry, (Great Britain: Bristol, Bristol Classical Press, 1982) 264Campbell maintains Sappho is trying to place Aphrodite in ‘her Olympian home’ and cites multiple allusions to such colored thrones of the gods listed in the Iliad and odyssey.79 Ibid Sappho was clearly aware of the Epic tradition, and this reading is not wrong. In the other song I am using in this project she makes direct reference to Helen, and her pilgrimage to Troy.80 Sappho, Fragment 16 Line 6Rayor and and Lardinois thus establish Aphrodite on her throne as a powerful goddess, one whom the speaker will continue to emphasize as powerful throughout the song. In their reading of ποικιλόθρον they are not only translating, but also choosing a different textual tradition over another. However, this is not the only word the Hymn to Aphrodite begins with, and Rayor and Lardinois note that other possible meanings are ‘with thoughts of many kinds.’81 Diane Rayor and André Lardinois, note to, Sappho: A New Translation of the Complete Works trans by Diane J. Rayor and André Lardinois (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014) 97

The Hymn to Aphrodite survives to the modern day with two different manuscripts, containing different words for the first word of the first line, adding to complexity to translating the Hymn to Aphrodite.82 Ibid 83Anne Carson notes to If Not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho trans. by Anne Carson (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2002) 357Anne Carson choses the other reading of the text, and uses the other word listed. Carson uses the word ‘ποικιλόφρον’ (poikilophron) instead, and bases her English translation off of that. For those who do not read an ancient Greek alphabet, this is the difference between poikilothron (used by Rayor and Lardinois, and Campbell) and poikilophron(used by Carson). It’s not a huge difference, and either sound is similar enough to maintain the metrical form of the line; but the word ‘ποικιλόφρον’ means ‘multi colored (poikilo) mind (phron).84Ibid Carson renders this as ‘of the Spangled mind’. Campbell also lists the word poikilos as ‘multi colored, spotted or dappled’85 David A. Campbell, Greek Lyric Poetry, (Great Britian; Bristol, Bristol Classical Press 1982) 264; but he does not accept Carson’s ‘phron’. Neither translation is wrong, but Carson explains her decision in her notes on the translation, stating she ‘prioritizes Aphrodite’s spangled mind because of the next line of the song, which describes how Aphrodite ‘weaves lures’’ or twists the minds of men. This double implication of mind was evidence for Carson to emphasize the connection of mind over throne. The thematic connection to the next line for a reading of ποικιλόφρον is something Rayor and Lardinois cite as possible for a reading of ποικιλόφρον rather than ποικιλόθρον.86 Diane Rayor and André Lardinois, notes to, Sappho: A New Translation of the Complete Works, trans by Diane J. Rayor and André Lardinois (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014) 97Carson decides that ‘Aphrodite’s Agile mind’ is what most of the song is dedicated to, so she emphasizes that.87 Anne Carson, notes to, If Not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho, trans, by Anne Carson (New York: Alfred A Knopf, 2002) 357

The first word of the only complete song of Sappho is thus a debate. This is not a bad thing, complexity does not reduce Sappho and it is essential to understand the multiplicity of Sappho. There are different manuscript versions of her songs, and thus different translations and interpretations. It just further illustrates how Sappho’s beauty is a shifting one, its meaning is subjective. The first line of the Hymn to Aphrodite finishes in a less controversial way, it reads ‘ἀθανάτ Ἀφρόδιτα’. Both of these words ‘ἀθανάτ’ and ‘Ἀφρόδιτα’ are also well known, but here it is more of a matter of translation than difference of manuscript. The literal meaning of the word ‘ἀθανάτa’ is ‘deathless’. It is an adjective used often to describe gods, as divine beings that do not die. Carson does render it as ‘deathless’ in her translation, but Rayor renders ‘ἀθανάτa’ as ‘immortal’, which sounds more natural in English. Again, both meanings work it is just the choice of the translator to choose metaphorical or more literal translations.

Continuing to the next line, Rayor and Carson’s translations both continue the negotiation between composition and replication of the Greek. Line two of the Hymn to Aphrodite reads:

‘παῖ Δίος δολόπλοκε’

Again, these words are not as controversial as ‘ποικιλόθ/φρον’, The first part of the line simply establishes Aphrodite’s pedigree as a powerful goddess; it reads ‘female child of Zeus’. Rayor and Carson both translate the phrase as ‘child of Zeus’, for ancient Greek it is straightforward. ‘Child of Zeus’ then has an additional adjective added to complete this phrase, which helps to define how Aphrodite uses her power, according to Sappho’s speaker. This adjective, ‘δολόπλοκε’ is often rendered in Greek dictionaries as ‘weaving wiles’.88 Liddell and Scott’s Greek English Lexicon, s.v., ‘δολόπλοκε.’ Many others, such as Rayor, Lardinois, and Campbell also translate δολόπλοκε as ‘weaving wiles’ The word is formed from the verb pleko (to twist, weave, bend, braid),645and the prefix dolon, (a lure ).89 Liddell and Scott’s Greek English Lexicon, s.v., ᾽πλέκω᾽; and ‘δολόν Rayor and Lardinois render it as ‘weaving wiles’ which is a more metaphorical translation, perhaps better understood in modern English. Carson again retains more of sense of the original Greek with ‘who twists lures’.It is δολόπλοκε which Rayor as justification for ‘ποικιλόφρον’ instead of ‘ποικιλόθρον’, as reference to the multi-colored mind that Aphrodite employs to bend the minds of others.90 Diane Rayor and André Lardinois, notes to, Sappho: A New Translation of the Complete Works, trans by Diane J. Rayor and André Lardinois (New York: Cambridge University press, 2014) 97An adjectival phrase that means ‘lure-braider’ is hard to render in English, and again both translations end up with different compositions for the same short word. Sappho sang in a context where her audience both had deep grasp of the language, but also cultural context. So much of the struggle to translate Sappho into English is recreating a lost context, especially in the case of fragments where more than just the context is lost, the work itself is. Adjectives like δολόπλοκε become hard to render. When translating all meaning cannot be imparted and translators prioritize different aspects that meet their goals in English composition.

The second line of the first stanza of the Hymn to Aphrodite concludes with the words ‘λίσσομαί σε’, a phrase where both translations agree. This phrase is fairly uncomplicated, as both Rayor and Carson translate it as ‘I beg you’. Here, even though Rayor and Carson have different goals in their composition, they convey the same message. Yet even though they agree, no translation is fully ‘right’ with Sappho; ‘λίσσομαί σε’ could just as easily be translated as ‘I pray, I entreat, I beseech’ into English.91 Lidell and Scott’s Greek-English Lexicon, s.v., ᾽λίσσομαι’᾽The use of ‘I beg you’ in both translations is most likely employed with the overall construction of the song. Campbell notes that the song itself is written ‘as a prayer, with the use of many epithets addressing Aphrodite, and reference in later lines to the fact that Aphrodite has aided Sappho’s speaker in the past’.92 David A. Campbell, Greek Lyric Poetry, (Great Britian: Bristol, Bristol Classical Press, 19982) 264-265The first couple of lines of the first stanza then open the song by placing it in context, and beginning themes seen through the rest of the work of Aphrodite’s power, and her pre-existing relationship with the goddess. So Rayor and Carson employ ‘I beg you’ as a form of prayer. This is fitting, as λίσσομαί σε’ transitions the stanza from stating Aphrodite’s power to what the speaker wants the goddess to do for her.

The third line of the song is an appeal to the goddess, one for mercy, though what Sappho’s speaker wishes to be spared from takes on nuanced differences in both translations. The third line reads: μή μ’ ἄσαισι μηδ’ ὀνίαισι δάμνα (mey m’asseyesee maid oneeeyesee dammna). It can be interpreted as an order, or a plea from Sappho’s speaker, the words: ‘μη // μηδ’ are a parallel negative construction, and can be read as ‘ Do not… // Nor…”. They are imperative, and meant to be used in command. In the context of a prayer, and with Carson and Rayor’s translation of ‘I beg you’ it is more like a plea. So, going forward Sappho sings ‘ I beg you, Do not ,’ then lists what things she most wants the goddess to help her avoid. The following word ἄσαισι (asseyesee) is a verb, often a medical term, which usually means to ‘feel loathing or nausea’.93 Lidell and Scott’s Greek English Lexicon, s.v., ‘ἀσάω‘ 94David. A Campbell, Greek Lyric Poetry, (Great Britian: Bristol, Bristol Classical Press, 1982) 265Here Campbell connects it to ‘ὀνίαισι’(oneeyesee) which is the plural Aeolian spelling of ἀνία (ahn-ee-a), meaning grief or heart break. Δάμνα (damna) is another Aeolian spelling of δάμνημι (damneymee), a verb that means ‘to conquer break, or subdue’.95 Ibid 96 Lidell and Scott’s Greek English Lexicon, s.v., δάμνημι The last two words in the stanza are πότνια (potkneea) and θῦμον (thewmon). Πότνια a title used for goddesses, it’s an honorific that’s best translated as ‘mistress, queen, lady’. 97 Liddell and Scott’s Greek English Dictionary, s.v., ‘πότνια’‘θῦμον, or as its more typical word form, θυμóς, means roughly as Rayor and Lardinois translate it, ‘spirit’.98 Sappho I translated by Diane J. Rayor, and André Lardinois in Sappho: A New Translation of the Complete Works, trans. by Diane J. Rayor and André Lardinois (New York: Cambridge University Oress, 2014) 25-26 Thus, Do not sicken me, nor break my spirit. To go through the first stanza again, literally:

[of the] Many colored throne/ mind, deathless Aphrodite

Child of Zeus, twister of lures, I beg you

do not with sickening/sickness me nor break with griefs my spirit

O Lady

That is my own literal translation, if I was trying to put Sappho lyrically into English I might go with a more poetic:

Rainbow minded, deathless one, Aphrodite

Child of Zeus, weaver of seductive wiles, I beg you

Don’t make me sick, not with breaking heartsickness harm

My spirit, O revered one

As above, Rayor and Carson have to navigate between the past, archaic words and concepts – such as direct prayer and response to a god. They also have to navigate between words with multiple meanings, such as poikilo-ph/th-ron with its two different texts, but also ‘simple’ words like θῦμον; which has many different meanings. It is commonly read as ‘spirit’ but also means: ‘soul, the principle of life, feeling and thought, esp. of strong feelings and passion’.99 Liddell and Scott’s Greek English Lexicon, s.v., ”θυμός’With a disclaimer that I am not an expert on the word, I would define it largely as ‘the feeling, irrational part of the human spirit or psyche that governs emotions’. But how to convey that exactly, or the many different meanings at once in a song that also needs to convey the beauty of the original is the challenge of Sappho.

Rayor and Lardinois render the concluding lines of the first stanza by playing with the Greek word order, and arrives at a lyrical English composition. They translate the lines as ‘do not break my spirit, O Queen, with pain or sorrow’. This composition works well in the English, but it also works for a grammatical interpretation of the Greek. They take δάμνα as the principle verb, Do not break, and then takes θῦμον which she renders as ‘spirit’ with the word μ’ ἄσαισι, connecting the θῦμον from the concluding line with the word part μ’ (or με) as referring to the θῦμον. So then, ‘Do not break my spirit’, ‘πότνια’ is then translated as ‘O Queen’, which works for Rayor and Lardinois’s assessment of Aphrodite on a throne. They conclude the line ‘with pain or sorrow’ which is how they interpret ἄσαισι and ὀνίαισι. The composition sounds good in English, and retains a certain beat, both of which are stated goals of Rayor’s. A well-crafted English composition is achieved through their translation, one fine version is created. Carson creates another while taking a different approach.

Carson’s treatment of the third and fourth lines of the first stanza again retain more sense of the original Greek, but also highlight certain level of compromise that has to occur when brining ancient Greek into English. Carson’s translation of the lines read ‘do not break with hard pains,/ O lady, my heart’. Like Rayor and Lardinois, Carson places δάμνα first in the English translation of the line, ‘Do not break’ but then she takes ἄσαισι and ὀνίαισι as ‘with hard pains’. Both ἄσαισι and ὀνίαισι refer to pain, intense pain, so the ‘with hard pains’ plural interprets them both as nouns that follow the breaking caused by δάμνα. This translation reads in English as more archaic, the language seems old, and a bit foreign, which it is. Stylistically Carson often chooses older or slightly odd phrases that evoke the distant context of the poem, a point she underscores by presenting the ancient Greek next to her English translation. Like Rayor and Lardinois’s translation, Carson’s composition does an admiral job of imitating the Greek, but cannot fully capture it. Rayor, Lardinois, and Carson are very skilled translators, far more than I, but translating Sappho into English leaves so much off the page that only certain aspects remain. Carson chooses to read θῦμον as heart, which works just as well as Rayor and Lardinois’s spirit. This is emblematic of their translations as a whole, and of the nature of translating Sappho. There is some difference between heart, and spirit, but it is hard to find in a poetic context, and comes down to an individual’s feeling, and how they interpret and read the work itself. Sappho with all her skill allowed for many different meanings as she sang, as she spoke words that had many meanings. She sings with more variety today when much context is lost. It is only when she is placed definitely into English, that attempts at one definition or word force her to choose one meaning. As a translator of Sappho, it is a monumental task, and the difference in Rayor and Lardinois, and Carson’s translation highlights how different views of Sappho have been stressed, depending on what each translator wished to convey.

And this is just translating the static typed word into English, trying to retain musicality to something of the beat of Sappho is another challenge. As I will be singing a translated version of Sappho’s songs, I am also looking at how people translate Sappho’s fragments back into the music they once were. Chris Mason, in his article on translating Sappho into English songs describes this challenge. Mason speaks of how in emulating Sappho as part of a larger American folk music chorus, he replicates lyres with banjos and other folk instruments.100 Chris Mason, “Bright Lyre Becomes Voice: Translating Sappho into Songs,” The Antioch Review 67, no. 1 (2009): 108 He also performs in some of the situations Sappho would have had her songs sung, at weddings and festivals, at parties.101Ibid He also speaks of the difficulty of rendering her songs into English while maintaining the sound and beat of the original Greek, which is an important consideration.102 Ibid 109Though I will be singing in Ancient Greek I will also be doing so in English, to further the idea of Sappho’s work being more accessible. Mason states how he tries to –re-create the word sounds of the Greek into English, a concern Rayor also has with her translation.103 Ibid 104Diane Rayor, introduction to, Sappho: A New Translation of the Complete Works, trans. by Diane J.Rayor, and André Lardinois (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014) 1

To better examine this I am going to analyze the phonetic sounds of the first stanza, and then attempt to replicate them in a good translation. For those who do not read the Greek, I am transliterating them into here, stressed syllables according to the meter are in bold:

poikeylophron (poikeylothron) athawknot’ Aphroedita

pie deos dolloplowkay, lissoemy sey

mey m’ assaisee meyd onyaisee damna

poe-tnia thuumon

Even transliterating from ancient Greek into English is difficult, because it relies on a knowledge of ancient Greek word and vowel sounds that the average English speaker does not have. Sappho is tricky to communicate. The above transliterated stanza serves as an example of both the meter’s beat, and how it was stressed, following a metrical pattern of:

long/short/long/short-long/short/short/long-short/long/long-

long/short/long/short-long/short/short/long-short/long/long-

long/short/long/short-long/short/short/long-short/long/long-

long/ short/short/ long/long

Here I use / to distinguish between different beats in a line, and hyphens to represent distinct metra. In a diagram of meter the pattern would be

-U-U/-UU-/U–

-U-U/-UU-/U–

-U-U/-UU-/U–

-UU–

Thus to make a translation that is metrical, but also mimics the original Greek in both sound and sense is really challenging. It is hard to get a ‘full’ idea of what the words of Sappho sounded like, ignoring the fact that the accompanying music has been lost. In trying to come up with a translation that replicates the sounds and stress of the Greek words a little better I arrived at:

Multi-colored minded one, without death, Aphrodite

Sion of Zeus, lure twister, listen to me, I pray

May you not sicken me may you not break grievingly

O powerful weaver, this soul inside me

This translation is lacking, though in word choice like ‘listen to me, I pray’ I imitate the Greek of ‘lissomai sey’. Like the Hymn to Aphrodite’s unnamed woman who inspires the song, Sappho’s sense is hard to capture. Others more skilled than I have tried though, Stephen Diatz has also put the hymn to Aphrodite in pitch accent, in which a raise in pitch would indicate a long beat. For more on this, please consult my blog post concerning these issues

I have already spoken at length about meter and what it meant in the ancient world, o I will not engage in those issues here. What becomes clear after all of this is the difficulty of rendering Sappho. She escapes perfect clarity, or singular definition. Even with my lyre, I cannot hope for full accuracy. This project is very deeply a work of modern re-creation of notions of ancient practices, but even through the millennia (and my lack of knowledge and skill) Sappho’s beauty is clear.

Here Sappho’s skill are on full display. She creates an introduction for the rest of her song to rest off of, making allusion to Aphrodite’s power and parentage. Her word choice is beautiful, even in the English. Here is a woman, calling on a goddess of either a rainbow mind or throne to aide her, to protect her from the worst pains, that of heartbreak. The poem in its entirety is capture in both translations above, and her skill, aided by the translators, still shines through. What makes Sappho so enduring is the beauty of her work, but also its universality. Perhaps people no longer beg Aphrodite for aid today, but many still pray for release from heartbreak. Her skill conveys a message that still applies. Sappho’s skill is continued throughout the rest of the poem, her word choice is exquisite. Additionally, though it is difficult to render in the English, the metrical beat of the line is beautiful, and equally difficult to craft into lyric. Sappho is skilled in the creation of narrative, she has her speaker appeal to a powerful, dangerous goddess, for help in a dire matter. This goddess responds, though notes that Sappho often has these problems, and guarantees that the object of Sappho’s affections will soon also experience some sort of heartbreak as well. The poem concludes with the speaker Sappho calling on the goddess to ‘be her ally’ as it usually rendered in English.105 Sappho I translated by Diane Rayor, and André Lardinois in Sappho: A New Translation of the Complete Works, trans. by Diane J. Rayor, and André Lardinois (New York: Cambridge UNiversity Press 2014) 25-26 1061 translated by Anne Carson in If Not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho trans. by Anne Carson (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2002) 2-5But this word ‘ally’ is actually a term for battle, specifically for a battle companion.107 Diane Rayor and André Lardinois, notes to, Sappho: A New Translation of the Complete Works, trans by Diane J. Rayor and André Lardinois (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014) 97 108The word is σύμμαχος (sumahkos), and literally translated means with (sum) fighter, fight, battle (mahkos/ mahey)- this is a situation so serious for speaker Sappho that she is calling for battle companions At first glance this word choice might be sarcastic, an attempt to portray the speaker as silly. But I think a better interpretation would be that the speaker is making the earnest claim that love and heartbreak is truly such a serious occasion that is requires battle companions. Sappho does not belittle love, she takes the human condition and its emotional state to be no laughing matter.

Sappho has considerable skill, which is clear in how manipulates

metaphor, language, meter, and word choice. The task of re-creating Sappho

relies on not muddying her shining work, not on improving it. Sappho is still

beautiful today, not because she is easily understood, but because when people

such as Carson, Rayor, and Mason fight to understand her, and make her be

understood by others, she shines. Sappho’s words endure because even with all

the technology and change since her own innovative time, people still

experience heartbreak. People still want to be free of sorrow, and appeal for

help, either from deities or other entities. The entirety of this project began

with the idea of making Sappho easier to reach, though in many ways she is

still beyond our grasp. Sappho has palpable beauty, and it is my hope that

anyone who interacts with her work (through this project or otherwise) will

soon pursue her.