Who was Sappho?

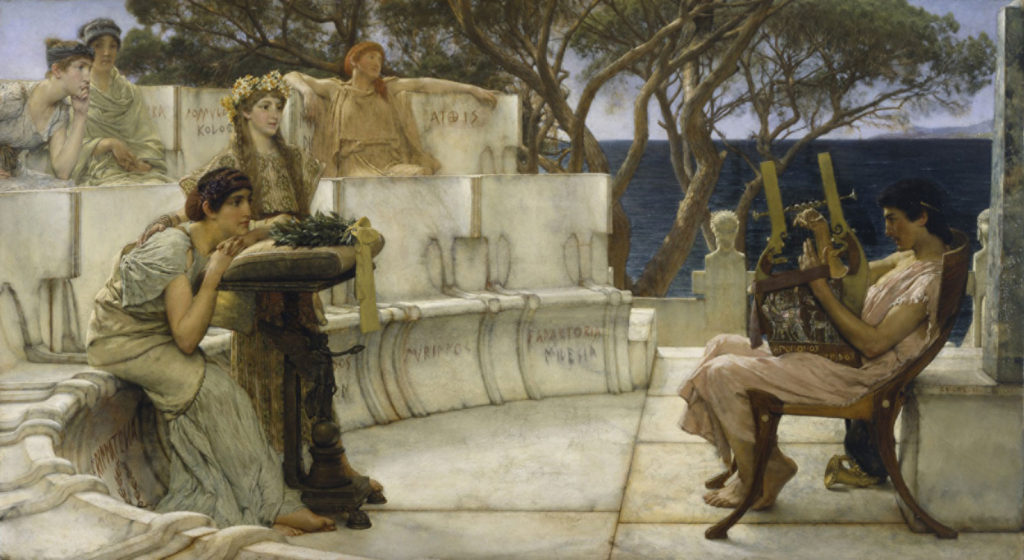

Who was Sappho? Sappho was a lyric poetess in 7th century BCE; very few concrete things can be said about her besides the great quality of her work. Sappho is known today through vase paintings, ancient testimonies, and her poetry.1 Sappho, Sappho: A New Translation of the Complete Works, trans. Diane J. Rayor and André Larndinois (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014) 1 She was from the island of Lesbos 2The modern day pronunciation is ‘Lesvos’ but as I am using pronunciations and spellings that would have been used in Sappho’s time , most likely from the capital city of Mytilene. 3Sappho, Sappho: A New Translation of the Complete Works, trans. Diane J. Rayor, and André Lardinois (New York: Cambridge University Press 2014) 5 Sappho was born around 630 BCE, and was reported to have produced nine books of songs.4 Ibid 3In ancient sources, Sappho is a noble woman, with three brothers, parents, a husband and a daughter.5Ibid, 3 This information is far from certain. Ancient evidence about Sappho is contradictory, and at times derogatory.6“For instance, the name of her husband is said ti have been Kerkylas of Andros…[which] means ‘Little Prick from the Isle of Man [in Ancient Greek].’ A reasonable oberserve might conlude this was not her husbands name.” Sappho, Sappho:A New Translation of the the Complete Works, trans. Diane J. Rayor, and André Lardinois (New York: Cambridge University Press 2014) 4. Sappho provides as many questions as she answers. Her function as a female Lyric poet on Lesbos, and what her life resembled is something scholars still debate today. 7Ewen Bowie, “How did Sappho’s Songs Get into the Male Sympotic Repetoire?”, in The Newest Sappho, P.Sapph Obbink and P.GC inv. 105 frs 1-4: Studies in Archaic and Classical Greek Song, Vol. 2, edited by Anton Bierl, and André Lardinois, (Brill 2016) 148 Not enough concrete information remains to fully place Sappho in her own context. Much of her work has been destroyed or forgotten, little of it survives. Sappho arrives in the modern era with a fragmented body of work, and a fragmented past.8 For more on Sappho’s biography, consult: Maarit Kivilo, “Sappho.” In Early Greek Poets’ Lives: The Shaping of the Tradition, 167-200. (Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2010). doi:10.1163/j.ctv4cbgkd.11. Most of her work has been lost, and what is known about her life needs to be heavily questioned.

The Tenth Muse

Though a lot is uncertain, it is true that Sappho was regarded as exceptionally talented in antiquity. She is often labeled the tenth muse by later Hellenistic writers. 9A.Gosetti-Murrayjohn. “Sappho’s Kisses: Biographical Tradition and Intertextuality in “Ap” 5.246 and 5.236,” The Classical Journal 102, no.1 (2006): 23 By calling her a muse, Sappho is elevated beyond the talented male composers who were her contemporaries. She is given ‘immortal and divine status’.10 Judith P. Hallett, “Sappho and Her Social Context: Sense and Sensuality.” Signs 4, no. 3 (1979): 447 Sappho was considered so gifted she lost her human nature, she became a god. Along with this, the famous Athenian king Solon is reported to have said he wished to learn Sappho’s poems, “So, once I learn [her work], I may die.”11Aelian, Fragment 187/190 (from Stobaeus 3.29.58) translated by Sentiaeantiquae, a website dedicated to making Classical literature more accesible. A special thanks to them for allowing me to use their translation of this passage. The link to the specific article is listed above, and their overall website is sententiaeantiquae.com Sappho was incredibly beloved. She was remembered for hundreds of years after her life, for her talented work, and other less positive associations. Though her prestige in antiquity is known, much of her work is now lost.

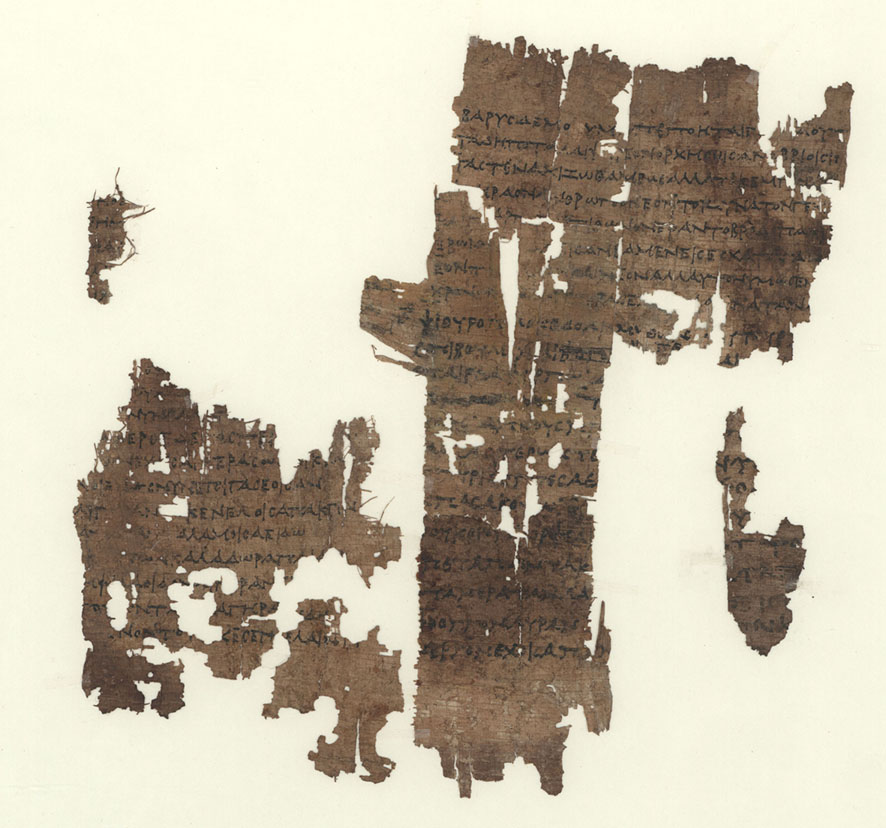

A Fragmented Past

The fact remains that most of Sappho’s work has been lost or intentionally destroyed.12 Jim Powell. The Poetry of Sappho, (Oxford University Press Incorporated, 2007) 45 Largely speaking, Sappho’s poems were compiled into nine different books in Alexandria between 300-200 BCE.13 Ibid. For more on the provenenance of Sappho’s work, please consult Dirk Obbink, “Sappho Fragments 58-59: Text, Apparatus Criticus, and Translation,” Classics Volume 4:Ellen Greene and Marilyn Skinner, eds. The Center for Hellenic Studies ofHarvard University, online edition of March 11, 2011. Sappho’s work also survives in different ancient dictionaries, noting her grammar and vocabulary, as well as in quotations by different ancient authors.14Jim Powell, The Poetry of Sappho, (Oxford University Press Incorporated, 2007) 45 Preserved in these sources her poems continued to influence later writers, but by 500-700 CE, Sappho’s work was no longer valued, no longer preserved.15 Sappho, Sappho : A New Translation of the Complete Works, trans. Diane J. Rayor, and André Lardinois (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014) 3 Most of her work was lost. There is no one answer for why Sappho became devalued hundreds of years after her fame and godlike status. One possible reason might have been that the Greek Sappho writes in – Aeolic Greek – is hard to understand, and that her poems may have lost popularity because of the difficult language. 16Jim Powell, The Poetry of Sappho, (Oxford University Press Incorporated 2007) 45. There were many different dialects of Ancient Greek. Sappho’s Aeolian dialect is the language that people from the Islands spoke, rather than the language of the Athenian mainland, Attic Greek. In later antiquity and the middle ages Attic greek was easier to understand, and more well known. For more on ancient Greek and its dialects please consult Companion to the Ancient Greek Language, edited by Egbert J. Bakker, (Wiley, 2010), specifically Olga Tribulato’s chapter on dialect. Another is that in the middle ages Sappho was regarded as a ‘love mad’ ‘female harlot’. There are also some reports of her books being burned by different Christian authorities, because of their erotic nature.17D.M. Robinson, (David Moore). (1963). Sappho and her influence. (New York: Cooper Square Publishers) 134. There seems to be some evidence that overall, Sappho’s books were later found to be too scandalous in a later christian society. for more on this consult Walter Penrose’s “Sappho’s Shifting Fortunes from Antiquity to the Early Renaissance,” Journal of Lesbian Studies 18, no. 4 (October 2014): 415-36 Later Christian authorities found her work, especially her erotic work, very threatening. Sappho was demonized as promiscuous, and her work was devalued.18 Walter Penrose’s “Sappho’s Shifting Fortunes from Antiquity to the Early Renaissance,” Journal of Lesbian Studies 18, no. 4 (October 2014): 421 Today, only one complete poem remains, and many poem fragments. But hope remains in 2014 more of Sappho’s fragments were discovered.19For more on this, consult The Newest Sappho, P.Sapph Obbink and P.GC inv. 105, frs 1-4: Studies in Archaic and Classical Greek Song, Vol. 2, edited by Anton Bierl, and André Lardinois, 2016. This is on of the first works on the newly published poems from the most recently discovered papyri fragments. It is possible that more will be discovered in the years to come, but even the fragments are incredibly beautiful, if largely obscure.

Sapphic Sappho

In the modern era, Sappho is not widely remembered for her work, but instead for the cultural impact she’s unwittingly had. Sappho’s writings about erotic desire between women is where the western world gets its terminologies for desire between women. The word lesbian originally means ‘a native of the island of lesbos’. 20It functions as ‘Bostonian’ does today in English, obviously with different connotations. For more on this please see ‘Lesbian.’ The Merriam-Webster .Com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster Inc. Interestingly enough, the modern day inhabitants of Lesbos do not appreciate this association, to the point where they attempted to sue the LGBTQ community of Greece, but the suit was unsuccessful. Sapphic and lesbian are both terms that come from Sappho, and her work.21For more on this consult: Encyclopedia of Lesbian and Gay Histories and Cultures, edited by George Haggerty, and Bonnie Zimmerman, (Taylor & FrancisGroup, 1999). If Sappho is known today at all, it is for being a famous lesbian. 22In Sappho’s own cultural context, she would not have been labeled a lesbian. The ancient world’s definition of sexuality was not as binary as ‘gay’ or ‘straight’ and it is unlikely she would have considered herself a lesbian at all. This does not mean her poetry which speaks about desiring other women is not valid, just that the identification of modern concepts with ancient people do not always align. For more on ancient sexuality Marilyn B. Skinner’s Sexuality in Ancient Greek and Roman Culture (John Wiley and Sons 2013) is a great resource. For more on how Sappho came to be understood in a more modern sexual context, and how those ideas developed please consult Susan S. Lanser’s Mapping Sapphic Modernity 1565- 1630 (University of Chicago Press: 2015) Throughout all of history Sappho’s work has become almost secondary to her gender and sexuality.23For more on Sappho’s gender and how it influenced her work and its perception please consult: Marilyn B.Skinner, “Women and Language in Ancient Greece or, Why is Sappho a Woman?”, in Reading Sappho: Contemporary Approaches (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996) 175-192; and Eve Stehle’s Performance and Gender in Ancient Greece: Nondramatic Poetry in Its Setting , (Princeton University Press, 1997). Sappho’s work can sometimes be lost behind the desire it expresses, and the gender of the one expressing it. Her gender influences how her words are interpreted Sappho is not just extremely talented – she is taboo, erotic, and hard to confine to any box. The goal of this project is not to re-interpret Sappho, or her work, or the implications of her gender on her work and influence. Enough scholars have done that, and continue to examine Sappho in new and interesting ways. The goal of this project is to examine Sappho as she is, by attempting to re-create an approximation of her work, and let the beauty of it speak for itself.

The Playing Sappho Project

When engaging in acts of historical re-creation, it is important to understand notions of authenticity. The past, to some extent, is always based on a fiction. 24David Dean, “Introduction,” A Companion to Public History. Ed David Dean, (Chichester UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd., 2018) 25. For more on public history, consult the entire book which is a great introduction to the topic. Today, she has many different voices and feelings, depending on how her work is read. though a fair amount about Greek lyric poetry is known, how Sappho performed it within her own context is in question.25Eva Stehle, Performance and Gender in Ancient Greece : Nondramatic Poetry in Its Setting (Princeton University Press, 1997) 72 Sappho survives today in fragments, which means all of her work has many different interpretations. There can be no one ‘True’ Sappho. Sappho holds many truths. Sappho’s role in it is also largely fragmentary. There can be no notion of an ‘authentic’ or ‘literal’ Sapphic lyric musical performance, because there is no concrete idea of what that might have been. In doing this project, I will have to keep in mind that many of the definitive choices I make in regards to style and application are ultimately just ones of opinion, with a lack of definitive fact.

This project consists of two parts: Part one is the building of a workable lyre, a barbitos. I am going to be making several prototypes, to practice building the barbitos. I will be making these prototypes using accessible and sustainable materials, not found in the ancient world. After I make these prototypes, I will make a final barbitos, made out of materials more similar to those used in ancient world. At no point should any of this be considered ‘a literal re-creation’, but there is not enough remaining evidence to guarantee authenticity. A literal re-creation is not the goal of this project. The goal is approximation. Part two consists of the vocal performance of Sappho’s lyric poetry. I will attempt to perform in pitch meter, and accent. I will also be performing in English some of Sappho’s work, to make it further accessible. The idea is that the song in the original meter with the playing of barbitos, comma will together more faithfully re-create Sappho than just the lyre, or just the vocal performance alone. Both are technical challenges, and I will not execute any of these tasks perfectly. I simply hope to help others learn how to do them, as well as learn myself.

Keeping all of this in mind about Sappho and lyric performance, the blog component of my website is going to document how I attempt to re-create Sappho’s performance. I am going to focus on the process of a modern re-creation of the barbitos, using for the most part modern materials and techniques. The barbitos has been selected for this project because it is heavily associated with Sappho and also relatively easy to construct. For this project, certain things must be ‘decided’ about the barbitos. I need to make definitive decisions about the barbitos I will build because very little about it is known. I will have to prioritize certain scholarly arguments in order to have a functional instrument. The instruments constructed for Playing Sappho are based in part off of the advice of Stefan Hagel, renowned ancient musicologist26Professor Hagel very generously answered my many emails, and his book Ancient Greek Music: A New Technical History is one of thebest works on the subject of Ancient Greek music. My deep thanks to him for continually answering the email of such a novice, and his patience in answering my questions. and his book. Helen Robert’s 1981 re-creation of the barbitos, and her arguments on stringing and playing theory also serve as a key reference. The barbitoi (plural of barbitos) I will make for this this project will have 7 strings of varying thicknesses, and be made out of materials like salad bowels and chair legs, in order to experiment with accessibility and design. I will also be experimenting with different theories on how the strings tied to the crossbar, and examining different string notation and playing.27There is a debate about how a 7 stringed instrument could play the full harmonic range that scholars believe was the foundation of Ancient Greek musical compilations. While I will be experimenting with some of these concepts, they are largely beyond the scope of this project as I will not be taking a definitive stance. For more on this please consult Otto Gombosi’s ” New Light on Ancient Greek Music.” Papers Read by Members of the American Musicological Society at the Annual Meeting 1939, 1939 , 168-83., also Helen Robert’s “Reconstructing the Greek Tortoise Shell Lyre.” World Archeology 12, No. 3, (1981): 303-12, also Stephen Hagel’s Ancient Greek Music: A New Technical History (Cambridge University Press, 2009) and Warren D. Anderson’s Music and Musicians in Ancient Greece (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1994)

As for the vocal part of the performance, I will be performing a combination of Sappho’s Hymn to Aphrodite, and Fragment 16. I intend to do this in an approximation of the original ancient Greek. This is not straightforward as ancient Greek is believed to have been a pitch language. There was a tonal pitch system, like those found in many Asiatic modern languages (such as Mandarin, Cantonese, Thai, to name a few). Pitch presents challenges in vocal recitation, especially for those only familiar with non-tonal languages, such as English. Some scholars28Stephen Daitz is the main source I am using to base my vocal re-creation of Sappho’s work on. Diatz was a noted scholar who worked in the re-creation of pitch accent and ancient greek vocal performance of the Iliad and Odyssey was groundbreaking. Diatz also re-created the vocal performance of the Hymn to Aphrodite, a poem by Sappho that will make up part of my final song, which I will use as a guide. have done re-creation work with pitch accent and ancient Greek; and I will use their work as a guide. In my recitation and performance of Sappho I am going to attempt to sing the original Greek in pitch (accent tone) and meter (tempo/ emphasis) as well as I possibly can. I also intend to sing in English as well, based off of the translations of Anne Carson, and Diane J. Rayor; in the interest of making this work more accessible

Ancient Greek Music: A Very Brief Overview

Ancient Greek Music is too complex to adequately describe in one paragraph on a website. It’s a tradition that spans hundreds of years, and has alot of musical theory behind it. For the purposes of this project it was a rich and storied thing with its own rules, practices, and history spanning back thousands of years. Broadly speaking there were an interlocking system of different octaves that had specific names and places, and in stringed instruments corresponded to certain strings and notes. 29 Greek music was highly technical and complicated, and the full interpretation of the scope of the greek musical system is beyond this project. for more on that please consult Warren D. Anderson’s Music and Musicians in Ancient Greece, (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1994). His book provides a good general knowledge, as well as giving examples of what the music would looked line in modern day notation. For a more technical overview, Stefan Hagel’s previously mentioned book Ancient Greek Music: A New Technical History gives an incredibly detailed description of the subject. The barbitos, the specific lyre I am re-creating, was one of many 7 stringed lyres on the ancient world. Several different systems of notes and melodies existed, with several different common chords being used. With regards to its notes and tuning, Stefan Hagel advised me to tune my barbitos to something along the lines of ‘B C# D E F# A B with A set to a pitch of roughly 245Hz’ and pure fourths and fifths’.30Stefan Hagel, email message to me, February 28th, 2019 Little is known about Sappho’s music, in fact her poems never reference the word barbitos, the lyre associated exclusively with her.31Warren D. Andersons, Music and Musicians in Ancient Greece, (Ithaca and London: Cornell Univeristy Press, 1994) 75. Anderson suggests this is because the ‘longer armed’ lyre was only named the barbitos later, the term ‘barbitos’ does enter the Ancient Greek language very late in the historical record. For more on the etymology of the barbitos please consult Jane McIntosh Snyder’s “The Barbitos in the Classical Period,” The Classical Journal 67, no. 4 (1972): 331-40. Much is known, or theorized about Ancient Greek Music today, and more work continues to be done.

Ancient Greek Lyric: A Very Brief Overview

Ancient Greek Lyric is roughly speaking, the practice of ancient Greek artists to sing songs while playing an instrument.32Mulroy in his book on early Greek lyric defines it as a musical performance style different from earlier styles, like that of Homer (Mulroy 1). For more on this and Greek lyric in general please consult David Mulroy’s Early Greek Lyric (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1992) It is important to note that ‘the ancient Greeks did not distinguish between song and poetry.’33David Mulroy, Early Greek Lyric (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1992) 9 This creates a situation in which most surviving Greek poetry is actually a song, without any surviving notes or melody.34Ibid; Stefan Hagel, email message to me, February 28th, 2019 Ancient Greek Lyric was broadly speaking divided into two categories, song with a singular speaker, or monody, and choral song.35David Mulroy, Early Greek Lyric, (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1992) 9. For more on this read Mulroy’s section on Lyric Form in his introduction Sappho is most heavily associated with monody36 Ibid , though she does also have wedding songs that are considered choral in nature.37Ibid, 87 In an overall context, solo performers would have performed at parties or banquets, while chorus’s had more ritualized settings.38Ibid, 10; André Lardinois argues in his chapter “Who Sang Sappho’s Songs?” in Reading Sappho: Contemporary Approaches (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996) that Sappho is more often a choral performer than a solo one, though her songs are from the perspective of a singular speaker. For more on this please consult André Lardinois’s chapter While a lot is known about male performers and what role they served, little is known about Sappho’s performances. There is a common conception of ‘Sappho Schoolmistress’, where Sappho served as a leader of a chorus of young women.39Claude Calme makes this argument in “Sappho’s Group, an Initiation into Womanhood,” in Reading Sappho: Contemporary Approaches (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996). Calme takes this argument as a given though Mulroy notes ‘suggestions that she [Sappho] was a teacher in a kind of finishing school…is pure speculation.’ David Mulroy, Early Greek Lyric,(Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1992) 87 Others analyze Sappho as a sole female performer in male drinking parties, or symposium, though there is equally little evidence for this.40Ewen Bowie argues this in “How Did Sappho’s Songs Get Into the Male Sympotic Repertoire?” in The Newest Sappho, P.Sapp Obbink and P. GC inv. 105, frs 1-4: Studies in Archaic and Classical Greek Song, Vol. 2, edited by Anton Bierl, and André Lardinois, (Boston: Brill, 2016). Bowie argues that Sappho mostly performed at male drinking parties as a singular woman performer. While I am ultimately not swayed by his argument, it is a useful counter argument to the idea of ‘Sappho Schoolmistress’ which is sometimes accepted too easily. Ultimately, what Sappho’s performance was is theory and speculation. This means recreating her performance largely guesswork.

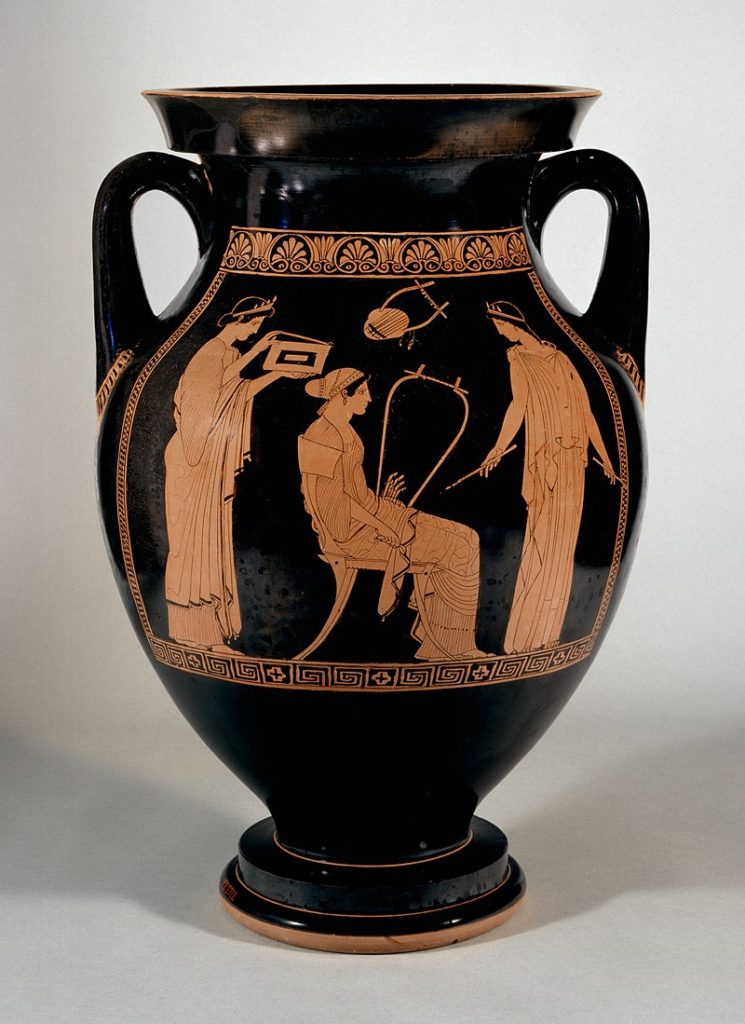

What is a Barbitos?

The barbitos is a larger lyre41 Maas, and Snyder Stringed Instruments of Ancient Greece, (New York, New Haven: Yale University Press 1989) 111 , a lyre is a term for a string instrument composed of a drum, and wooden arms. The barbitos is made of a tortoise shell and goat skin drum, two wooden arms, a cross bar, and 7 strings hung parallel, attaching to the drum. A helpful way to conceptualize it is as an ancient banjo, one with two arms.

Meter: A Very Brief Overview

-U-x-U U-U- – xx-UU-UU-UU-U- -U-x-U U- -U U-U- –

Meter is the scansion of the line, or how fast/ slow something is said with regards to the lines syllables and beats. A good way to conceptualize meter is to think of the song ‘Camp Town Races’ and attempt to sing it with the same beat as ‘jingle bells’. It sounds wrong, not because any musical rules are necessarily broken, but because the meter that is associated with ‘Camp Town Races’ is not the same as jingle bells, and it sounds dissonant. Ancient Greek was a highly metrical language, and the use of meter and form greatly determined how lyric poetry functioned.42 Sappho used the Sapphic Stanza, along with other metrical forms, but the Sapphic Stanza is the one most associated with her. The lines of a Sapphic Stanza composition has a metrical beat of: -U-x-U U-U- – xx-UU-UU-UU-U- -U-x-U U- -U U-U- – where – represents a long syllable, U represents a short syllable, and x represents a syllable that can be long or short. This metrical diagram is from The Meters of Greek and Latin Poetry by Halporn et all (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1980) 132. For more on meter, consult the book in its entirety. In ancient Greek plays, songs, and scripture, meter could deeply affect the mood of what a character was saying, or be manipulated to enthrall or frighten an audience. Sappho’s work now largely functions as written poetry; but that does not mean its meter is any less important. In performing Sappho in a vocal context, I am going to pay special attention to the meter of the lines, in order to re-create her work as best I can.

Sappho’s Work Itself

Sappho’s work is thousands of years old, but still striking today.43 Unless otherwise stated, all following opinions about the quality of Sappho’s work are my own. As previously mentioned, Sappho has many different interpretations and I am not an authority on her work. Her work has a timeless quality; it covers love44 Sappho, Hymn to Aphrodite line 16 ‘What have I suffered again,’ here Sappho recounts falling in love again, as if it’s a malady; Sappho, Sappho a New Translation of the Complete Works, trans. Diane J. Rayor, and André Lardinois (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 20 , loneliness, loss45Sappho Fragment 16, lines 16-21, I will engage more thoroughly with this poem shortly, but here Sappho expresses a deep desire for a love no longer present. Though because it is a fragment there is no certain conclusion, this loss seems permanent, she will never see her love again. Compared to fragment 31 where Sappho has to endure seeing someone she loves but cannot have; though there is a possibility that these fragments refer to the same person, given the lack of a complete composition., desire46 Sappho Fragment 23 Sappho a New Translation of the Complete Works, trans. Diane J. Rayor, and André Lardinois (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014) 39 , shame, and yearning.47Sappho Fragment 31, Ibid 44. Sappho here expresses desiring someone who is not with her, a lover who has perhaps taken a husband. She cannot speak, ‘I can say nothing/ My tongue is broken’ she both yearns for her lost love and feels shame as if ‘I seem/needing but little to die’. Even though the world today is vastly different from the one Sappho knew, heartbreak and loss are still understood. Sappho even comments on her old age, another problem that people still struggle with.48 Sappho Fragments 21 (Ibid 37), 24 (Ibid 40), 58 (Ibid 54), all speak of aging. for more on Sappho and mortality please consult: Ellen Greene and Marilyn B. Skinner, eds. The Newest Sappho on Old Age: textual and Philosophical issues, Hellenic Studies 38. (Washington, DC: Cambridge, Mass: Center for Hellenic Studies, Trustees for Harvard University; Distributed by Harvard University Press, 2009). Sappho speaks of how ‘my skin was delicate before, but now old age [claims it]’49 Fragment 58, Ibid 54 , though Sappho’s conclusion is far from despairing over her age. The Fragment concludes on ‘Yet I love the finer things…this and passion/ for the light of life have granted me brilliance and beauty.’50 Fragment 58, Ibid lines 15-16 Sappho not only repeats the common suffering of being human, but she inspires people to graceful and appreciating aging. Like all of Sappho’s words, its message still applies. Sappho advocates for honoring a beauty beyond the physical, though she also has a deep appreciation for physical beauty.51 Sappho Fragment 41 ‘For you my beautiful woman my mind/ never changes’ Ibid 47 Sappho is ultimately correct when it comes to her own beauty; as her beauty and passion extend even beyond the death and decay of her physical body. Thanks to her work, she is eternally beautiful.

Sappho is far from perfect, she represents other feelings and situations besides love and loss. She has bitter words for others as well.52 Sappho Fragment 91, ‘I never met anyone more irritating, Eirana, than you’ ibid 63. She has more: Sappho Fragment 55 ‘When you die you’ll die dead. No memory of you,/ No desire will survive, since you’ve no share/ in the Pierian roses. But once flown away/ You’ll wander among the obscure dead, invisible in the house of hades,’ Ibid 52. Sappho also expresses jealousy, in fragment 57 she proclaims ‘ What country woman bewitches your mind…/ wrapped in a country dress…/too ignorant to cover her ankles with rags?’ ibid 53. Sappho also has much longer poems chastising her brothers for their actions. There may be more ritualistic reasons for Sappho’s critiques, they may have deeper implications in a lost cultural context. For more on this, please consult Melissa Mueller’s “Re-centering Epic Nostos: Gender and Genre in Sappho’s Brothers Poem.” Arethusa 49, no.1 (2016): 25-46. Sappho is deeply human, and expresses human thoughts and feelings from a singular speaker’s view, when much of Lyric poetry was choral.53 Sappho, Sappho a New Translation of the Complete Works, trans. Daine J. Rayor, and André Lardinois, (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 2. 54 Diskin Clay, “The Theory of the Literary Persona in Antiquity,” Materiali E Discusioni per L’analisi Dei Testu Classici, no. 40 (1998): 10. doi:10.2307/40236116.10; Literary Persona essentially means the character a writer creates in a body of work, not necessarily representing themselves. It is worth noting that the ancient greeks themselves perceived all spoken Lyric poetry to be a true representative of self, though Clay argues for a deeper reading into Ancient Literary Persona, and that there was a difference between a public performer performing and necessarily their true thoughts and feelings. For more on this consult the article in its entirety. Her singular voice shines through and still applies today, offering all the beauty and bitterness people still experience. In Sappho, we can see ourselves .

Sappho also provides a voice to the wants and needs of an upper-class woman 2,800 years ago, a perspective which is incredibly rare in ancient literature. This perspective is not necessarily her own. Sappho’s poems seem to be from the point of a singular female speaker named Sappho, but there is no guarantee this is the ‘real’ Sappho.55 David Mulroy, Early Greek Lyric, (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1992) 88.

Whoever the ‘real’ Sappho

is, she created beautiful art. To better explain her skill, I will be taking

the reader through a brief overview of Sappho’s fragment 16 to provide an example.

I’m selecting this poem for its beauty, and because it will be part of my final

vocal performance. The poem is also very expressive of Sappho’s style as a

whole.

Sappho Fragment 16

The following Greek and English comes from Anne Carson’s If Not Winter: Fragments of Sappho (New York: Yale University Press 2002) 27-28

![Poem of Sappho's translated and transcribed in the greek by Anne Carson it Reads: Οἰ μὲν ἰππήων ςτρότον, οἰ δὲ πέσδων,

οἰ δὲ νάων φαῖς’ ἐπ[ὶ] γᾶν μέλαι[ν]αν

ἔμμεναι κάλλιστον, ἔγὼ δὲ κῆν’ ὄτ-

τω τις ἔραται

πά]γχυ δ’ εὔμαρες ςύνετον πόησαι

πά]ντι τ[ο]ῦτ’· ἀ γὰρ πολὺ περςκέθοιςα

κάλλος [ἀνθ]ρώπων Ἐλένα [τὸ]ν ἄνδρα

τὸν [ άρ]ιστον

καλλ[ίποι]ς’ ἔβα ‘ς Τροΐαν πλέοι[ςα

κωὐδ[ὲ πα]ῖδος οὐδὲ φίλων το[κ]ήων

πά[μπαν] ἐμνάσθ<η>, ἀλλὰ παράγαγ’ αὔταν

᾽ ] ςαν

] αμπτον γάρ [

]…κούφως τ[ ] οη . .[ .] ν

.. ] με νῦν Ἀνακτορί[ας ὀ]νέμναι-

σ’ οὐ παρεοίσας,

τᾶς <κ>ε βολλοίμαν ἔρατόν τε βᾶμα

κἀμάρυχμα λάμπρον ἴδην προςώπω

ἢ τὰ Λύδων ἄρματα κἀν ὄπλοισι

πεσδομ]άχεντας.

]. μεν οὔ δύνατον γένεσθαι

].ν᾽ ἀνθρώπ[…(.) π]εδέχην δ᾽ ἄραςθαι,

[ ]

[ ]

[ ]

[ ]

[ ]

προς[

ὠςδ[

…].[

.].[.] ωλ . [

τ᾽ἐξ ἀδοκεἠ[τω.

in the greek and:

Some men say an army of horse and some men say an army on foot

and some men say an army of ships is the most beautiful thing on the black earth. But I say it is what you love.

Easy to make this understood by all.

For she who overcame everyone

in beauty (Helen)

left her fine husband

behind and went sailing to Troy.

Not for her children or dear parents

had she a thought, no –

] led her astray

] for

] lightly

] reminded me now of Anaktoria

who is now gone.

I would rather see her lovely step

and the motion of light across her face

than chariots of Lydians or ranks

of foot soldiers in arms.

]not possible to happen

] to pray for a share

]

]

]

]

toward [

]

]

]

out of the unexpected

in the english](http://playingsappho.collegeofwooster.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Screen-Shot-2020-01-12-at-11.08.34-PM-1024x1014.png)

What comes through in this poem is the longing Sappho’s speaker has for her absent love, and her elevation of love’s beauty over military force. It can be interpreted as the elevation of love over what a traditionally masculine culture found beautiful, might, power, conquest. Sappho also uses the example of Helen to make her argument that love is not an escapable force, sighting that she was compelled to go to Troy.56Helen is also a very powerful and often times scorned women in Ancient Greek thought, though more mythic than Sappho. For further implications on Sappho’s use of Helen to prove the compelling nature of love consult Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer’s “Shifting Helen: An Intepretation of Sappho, Fragment 16 (Voigt),” The Classical Quarterly Vol. 50, no. 1 (2000): 1-6; and Eric Dodson-Robinson, “Helen’s Judgement of Paris, and Greek Marriage Ritual in Sappho 16,” Arethusa 43, no. 1 (2010): 1-20 doi:10.1353/are.0.0032. Ultimately, it is her longing for Anakatoria, this face that she cannot see, this most beautiful thing that is outside of her grasp that compels this poem. As I will explain in a later blog post, this fragment is a favorite of mine and will compose the second half of the song I intend to sing. It is profoundly beautiful, as it speaks of unattainable beauty, even in the face of a force so compelling it is enough to start wars. Love cannot compel Anaktoria back to Sappho, or Sappho to her. And so, this beautiful face, the most beautiful thing is gone from Sappho. And it is this sweet bitter57 Sappho, Fragment 130, trans. Anne Carson, If Not Winter: Fragments of Sappho (Alfred A. Knopf 2002) 265 sensation that I find so endlessly compelling.